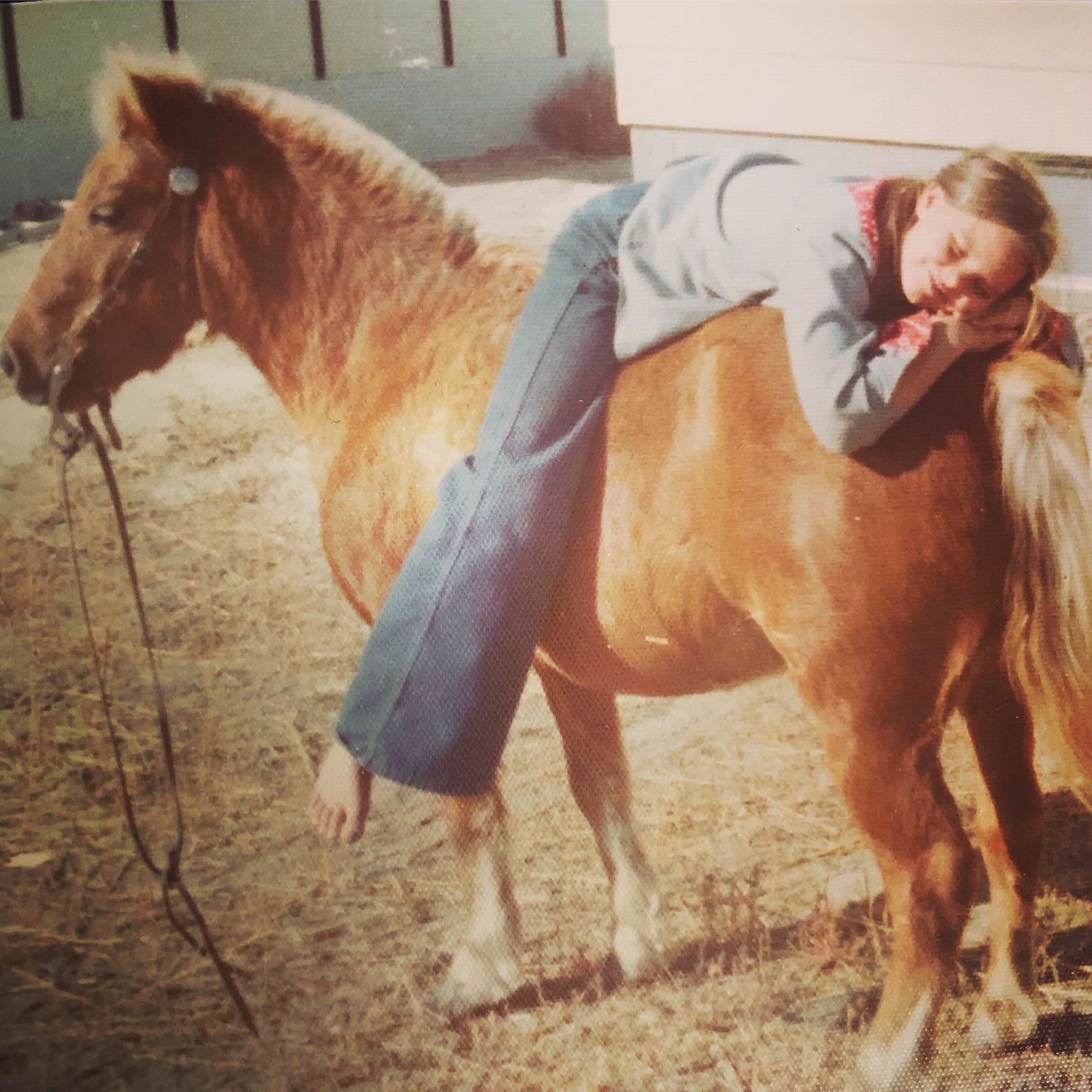

I was raised in poverty, in the wild and beautiful mountains of central Idaho, so I like to say I grew up in scenic poverty.

That pushed me to an interest in economics and the inner workings of the systems that structure our lives.

The Political Economy

The United States is the wealthiest country in the world, and we have one of the largest wealth gaps of any highly industrialized country. Wealth inequality is, in fact, very American.

The entertainment industry isn’t separate from the U.S. political economy—it’s one of its most expressive symptoms. Entertainment is a microcosm of the macro system, and we are uniquely and intricately woven into this economy.

Our economic system in the U.S. is a mixed-market economy with its foundation in Capitalism. There are two dominant ideologies when it comes to political economy – ‘Free Market’ developed by Milton Friedman and ‘Keynesian Economics’ developed by John Maynard Keynes. The U.S. is a mix of the two, providing free-market capitalism and a dose of social welfare that offers programs such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Services (Food Stamps, TANF, SNAP, etc).

Our ‘political economy’ is an intersection of law, policy, tax systems, market economy, and social and corporate welfare (more on corporate welfare down the page). Some things to note: 10.5% of Americans live below the poverty line, and the ‘poverty line’ was established in the 1960s. Children are the poorest individuals in the country, with 14.4% of children living below the poverty line. The ‘Working Poor’ (full-time workers who remain below or right at the poverty line) are another significant share of the political economy.

These numbers adjust depending on the community you hail from – poverty does travel differently through varying communities via racial and ethnic lines. Following the conception of the country, and the tremendous economic disadvantage of many, I think it’s important to understand the intersectionality of political economy – the darkest institutions in U.S. history: slavery, Jim Crow laws, and systemic racism in banking, education, housing, and industry have impacted generational economic gain.

Political economy cannot be separated from history…

Land, Labor & Capitalism

The American economic system was created with Capitalism as the goal.

In Europe, before the ‘migration’ to this land (don’t get me started), Feudalism was a land-based system of power, loyalty, and protection, where kings, nobles, knights, and peasants each played a role in maintaining a deeply unequal but structured society.

This underlines the seizing of the Americas… it was and always has been about the land. These European roots in Feudalism drive the conceptual foundation of the economy and the underlying ‘land grabbing’ of the systems of Capitalism. Getting all you can is a Capitalist, and thereby American, value.

One way that America built its foundational wealth was by creating federal agencies like the Bureau of Land Management, which was the formal design for stolen land. Its predecessors were the General Land Office (GLO), established in 1812, and the Homestead Act of 1862 (which the GLO administered), which were pivotal in seizing Native lands to become private property owned. Understanding how Capitalism and its value system shaped the economic base for the United States helps us understand how we fit into this system.

Another aspect of how we fit into history is the fundamental American view on poverty as the fault or responsibility of the individual. Crazy enough, this stems from the Elizabethan Poor Laws of the British Empire, which qualified poverty as such. This imprint has withstood centuries, and it underscores the way America functions from the standpoint of policy, law, and economic opportunity.

Franklin D. Roosevelt was one of the early presidents to truly address this structural poverty when he created the Social Security Act in 1935 after the Great Depression. And President Lindon B. Johnson was the next to design an anti-poverty charge in the United States when he created the ‘War on Poverty’. Inspiring to note: these changes were greatly influenced by the early social workers of the time, namely Frances Perkins, who was appointed by Roosevelt to serve in the presidential Cabinet, the first for a woman.

Where Those of Us in Entertainment Fit In

Entertainment is one of the country’s number one exports, following Aerospace. With the recent shifts in the industry, impacted by the pandemic, strikes, fires, and flyaway production, this is challenged. However, Hollywood, the media, music, and theater remain a steadfast part of what drives America’s creative economy.

The question of how we can sustain ourselves as artists and creatives is an ongoing factor. And there is the unavoidable truth that our industry has its own version of structural poverty. Understanding independent production and the journey of being an artist (or supporting artists) could be observed through a socio-economic lens. I think it’s important to understand the political economy and where we stand in it—and how our industry fits inside of it.

The conversation about sustainability has been ongoing for some time. It was striking to hear filmmakers Sean Baker and Brady Corbett speak truthfully about their own personal and professional journeys, and the lack of sustainability for even the highest-level, award-winning filmmaker.

Many of us have been contemplating Ted Hope’s non-dependent cinema (NonD

e) as a path to economic and creative sovereignty. Perhaps this is my #FilmStack Challenge of the Year – offering a social welfare or ethical tenet to what we are collectively creating. I am currently pursuing a Masters in Social Work, for the very purpose of working more effectively in Macro-systems. So, resonating with FilmStack’s First Principles #7, here is a hopeful value add for confronting structural poverty and working for the betterment of all.

It has also been impressive and inspiring to see what Producers United has done in a short amount of time to challenge the structural inequity that independent producers face (one of the few groups in the industry make-up that is not unionized). For the first time in my career, I received an early commencement wage on a project – something I would not have asked for had I not become a member of Producers United and followed the guidance and collective momentum of the group.

Although the leadership of Producers United may not see themselves as organizers in an anti-poverty movement, they, and all involved, have been fighting for something that addresses the structural poverty in our community.

We’ve come to understand the concept of anti-racist, that being non-racist is not enough, we need to take bold steps to confront racism in the system that surrounds us. Well, I propose that we, as an industry, also take strong positions against structural and endemic poverty. We need to actively engage in anti-poverty strategies and find powerful and effective ways to stand for one another.

We need ethics in our industry, a true value system that recognizes the value of people, of the worker. One that mitigates the overvaluing of celebrity, an odd extension of the monarchy. And one that is not complicit with the corporate welfare offered to studios and streamers (see corporate welfare appendix below!) Ultimately, finding pathways that offer collective strength and coalition building is a true power.

Elinor Ostrom was the political economist who theorized about collective action, governance, and the Commons. She greatly challenged Hardin’s 1968 theory of The Tragedy of the Commons, which suggested that human beings fail at collective self-governance. Because of her work upholding the Commons and pro-community sentiment, she was the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Economics, and she was a Los Angeleno. Ostrom’s thinking helps us to reframe how we think about resource sustainability, democracy, and human cooperation. She sounds like a good producer.

“What we have ignored is what citizens can do and the importance of real involvement of the people involved – versus just having somebody in Washington... make a rule.”

“Humans have a more complex motivational structure and more capability to solve social dilemmas than posited in earlier rational-choice theory.”

--Elinor Ostrom, 1930-2012

“I got fuck-you money, girl..”

--Post Malone

UNDERSTANDING CORPORATE WELFARE

Since the 1940s, the U.S. tax burden has shifted from corporations to individuals. In the 40’s, corporate income taxes made up 40% of federal revenue. By 2015, that number had dropped to just above 10%. The notion has been that lower corporate taxes help create jobs, but the truth is: people are still struggling, and economic inequality in the U.S. remains one of the highest in the world compared to other developed countries.

So, since 1940, the country has been moving steadily toward a cradle-state for corporations, and the American worker is carrying the load, leaving the true heart of the economy – the people – to contend with the complexity of sustaining a life.